Places Journal (

newly independent of Design Observer) recently published

an argument by Brian Davis and Thomas Oles that landscape architecture should be renamed landscape science:

“Slowly — fitfully — landscape architecture is remaking itself. Its adherents are venturing from the confines of garden, park, and plaza into strange and difficult territory, where they face challenges of a greater order. How will our cities adapt to rising seas? How do we respond to the mass extinction of our fellow species? How can we build places that are more just? Such questions mock the very notion of disciplinary boundaries…

Say it again: landscape architecture. The words roll off the tongue as if their union were inevitable. But this is an arranged marriage…

We need a term that updates Olmsted’s strategy of professionalization for the modern age. A term that is both broader and more specific, a term that can help simultaneously expand and focus the field. And for that there is only one real candidate. We therefore propose that landscape architecture become landscape science.”

This is ridiculously interesting and important.

I agree that there is a shift in both the scope and methodology of landscape research and practice underway. (That might actually

be the central concern of this blog.) Consequently, I think it is valuable to attempt to recognize that shift by naming and defining it. (The need for this shift is probably evident to any landscape architect of this emerging sensibility who has tried to explain their work to friends, colleagues, and family members who are not familiar with current trends in the discipline.) In the spirit of contributing to the effort to concretize that shift, then, I’ve named below three primary concerns that I have with the selection of

landscape science as worked out by Davis and Oles. Two of this concerns deal with the selection of the term science, while the third (the middle one, by order presented) questions what the relationship between landscape architecture and landscape science is in their proposal, and what it should be.

1 One of the most problematic components of the way that science is treated is its claim to objectivity; to be value-neutral. (We know from the philosophy of science that this is not entirely accurate; but it is perceived to be accurate.) Whereas one of the strengths of landscape architecture relative to other disciplines that make landscapes (logistics, engineering) is precisely that it has practices for making explicit, interrogating, and evaluating values.

1.

I am wary of elevating science in this fashion. This is often a rhetorical move that serves to marginalize other ways of knowing. This is potentially particularly problematic because science often equals “Western science”, and is consequently accompanied by the marginalization of non-Western ways of knowing. (See:

scientism,

positivism1.)

I know that Davis and Oles have anticipated this objection:

“Now we have opened a world of problems, not least that the word science brings its own conflicting associations… This has crowded out the original, more exciting definition.”

I’m not sure, though, that the likely effect of this (re)formulation of landscape science is to restore this earlier formulation of science, generally. It seems far more likely to me that the collective weight of the perception of

“scientific inquiry as the cold pursuit of quantifiable phenomena and material effects” will define how landscape science is perceived than the opposite. (And, indeed, to some degree the argument hinges on this: that landscape will gain some of the prestige that is accorded to sciences, precisely because they are perceived in this fashion.)

It seems problematic that the argument hinges on shifting the understanding of a concept back to 19th century terms; how often does this happen? Moreover, how often does it happen when the lever is the self-conception of a relatively small discipline like landscape architecture?

2.

Quoting Davis and Oles:

“Perhaps practitioners of a certain temperament will hold fast to the title of landscape architect, and that specific tradition might be understood as one important pillar in an expanding field of landscape science. People who study landscape science might be known as landscape architects, but also landscape geographers, landscape engineers, and landscape anthropologists (just as they have already started to claim titles such as landscape ecologist, landscape archaeologist, and landscape urbanist), or they might call themselves, more generally, landscape scientists.”

There’s something rhetorically problematic happening here. Should landscape ecology be seen as a subset of landscape architecture? I think not, though the fields are clearly related, both historically, methodologically, and topically; and I doubt that Davis and Oles think so, either. But if not, is the argument here perhaps really for a new umbrella that

includes landscape architecture, but isn’t a renaming of it?

2 It seems worthwhile here to also say: I am strongly in favor of

Alan Jacobs’ argument for (among other things) “self-consciously distinctive missions” and “pockets of resistance”, which seems potentially applicable to an effort the answer these questions. (Unfortunately, I think that an effort to claim science might radically undermine an effort to be such a pocket of resistance, because of the concerns I outlined in my first point.)

And if so: is that umbrella really a discipline? Or is a mode of operation? A shifting set of tactical alliances between fields that share interests, methodologies, and terrain? Something closer to transdisciplinarity than to a new discipline? If so, are we left in the same place that we started: needing a way to describe the operations (scope, methodology) of the set of researchers and practitioners that Davis and Oles mention (and others who have similar approaches)? Are we saying effectively that these people — as opposed to, say, the practitioners of landscape architecture who are primarily garden designers, or the plaza-makers who are outside architects — are the only ones who are landscape scientists? If so, why not generate another splinter discipline like landscape urbanism: between multiple disciplines, adopted by some practitioners, but not attempting to rename the whole discipline of landscape architecture? Isn’t this a more modest and practicable goal?

2

3 Moreover: to return to my first contention, I think it is precisely the quality of landscape architecture as making that positions the discipline as a useful alternative and/or augment (depending on the specifics of place and situation) to more positivistic ways of constructing landscapes, including

engineering and logistics.

I find myself continually returning to Dan Hill’s formulation about the value of design in

Dark Matter and Trojan Horses:

“the idea that policy and governance can be convincing through mere presentation of fact supported by clear analysis is also being directly challenged. In-depth analytical approaches can no longer stretch across these interconnected and bound-less problems, where synthesis is perhaps more relevant than analysis.

‘The problem is that transparent, unmediated, undisputable facts have recently become rarer and rarer. To provide complete undisputable proof has become a rather messy, pesky, risky business.

Design produces proof, yet as ‘cultural invention’ it is also comfortable with ambiguity, subjectivity, and the qualitative as much as the quantitative. Design is also oriented towards a course of action — it researches and produces systems that can learn from failure, but always with intent. In strategic design, synthesis suggests resolving into a course of action, whereas analysis suggests a presentation of data. Analysis tells you how things are, at least in theory, whereas synthesis suggests how things could be.”

“[design’s] core value… is addressing genuinely meaningful, genuinely knotty problems by convincingly articulating and delivering alternative ways of being”.

This also raises the point that “design” is perhaps being unhelpfully marginalized.

4 I think Davis and Oles acknowledge this, or at least are attempting to acknowledge it (I don’t think they explicitly say they are, so I may be misinterpreting), with the description of “what might its practitioners be called”? But the argument initially hinged on looking at the examples of radical practitioners, and whatever landscape architecture might be or might not be, certainly one of its strengths is that it is a practice. Renaming it in a way that requires a separate new term for the practice of it seems… inadequate. Which leads back to my second contention, about the proposed relationship between landscape architecture and landscape science.

5 This also refers to a point that geologist Brian Romans made

in reply to Brian Davis on twitter: that geomorphology might be the most fundamental of all landscape sciences.

It seems there are three possibilities inherent in a formulation of a landscape science: first, that landscape architecture becomes landscape science; second, that landscape architecture (as a whole) becomes a component of a new, broader discipline known as landscape science; third, that some components of landscape architecture (and other disciplines!) enter into a new set of alliances and develop a new set of practices-between-disciplines that might collectively be referred to as landscape science. It seems to me that the first is what Davis and Oles claim to be arguing for (

“we therefore propose that landscape architecture become landscape science”), but the last is what they are describing. (Not that I find that problematic! I actually find the last of these options most promising and most exciting.)

3.

My final objection concerns the centrality of making to landscape architecture. Recall the definition of science that Davis and Oles claim:

“a branch of knowledge or study dealing with a body of facts or truths systematically arranged and showing the operation of general laws; knowledge gained by systematic study.”

Science, even defined in this earlier way that does not make exclusive reference to the natural sciences or to the scientific method as a mode of knowledge production, is nonetheless an enterprise focused on

knowing. By contrast, landscape architecture is, at least in my opinion, not only a profession of making, but also a discipline whose core depends on

making. While making and knowing should not be perceived as being purely exclusive (in fact, I would argue that making can be a way of knowing — this is central to the notion of design as research), their overlap is far from entire. “Landscape science”, even defined as normative, does not seem much like making. And the practitioners that landscape science would claim (Orff, Cowles, Bargmann, to use Davis and Oles three examples) are clearly makers.

In the middle of their argument, Davis and Oles recommend that:

“…we should establish our own integrated science, with its own specific methods, concepts, and techniques. We can adapt tools from the many fields that already work with landscape as a primary object of inquiry, including archaeology, ecology, environmental studies, history, planning, psychology and sociology.”

But which of those methods does landscape architecture contribute to landscape science? It seems to me that one of the most obvious answers is: landscape architecture, unlike archaeology, ecology, environmental studies, history, psychology and sociology (I leave out planning, whose operations are more ambiguous and variable), makes, builds, fights

matter battles. If making is so essential to landscape architecture that it might be the discipline’s primary contribution to landscape science, then is it inadequate to choose a new name that does not acknowledge this

3?

I’m not sure that Davis and Oles further definition of landscape science as a normative science (“[according to Peirce], normative science ‘distinguishes what ought to be from what ought not to be’”) answers this objection. There’s a significant gap between

ought and

make4. (Do we really think that a maintenance worker is a landscape scientist? This seems to stretch the term terribly far.) Of course, we have a term for someone who applies science to make: a technician.

Landscape technics is an interesting alternative, not far removed from

Patrick Geddes and Benton MacKaye’s geotechnics5.

Perhaps the greatest disadvantage of technics is that the word is out of fashion, in much the same sense that science is in fashion.

4.

Having detailed these three concerns, it would be right of me to also list the things that I appreciate, because there is a great deal that I appreciate in Davis and Oles’ argument. I don’t know that it is necessary for me to go on in such detail about them, though, so I will simply say: that the array of benefits listed under section III is extremely desirable; that I agree that there is a great deal to be gained by not “privileging… architectural terms and concepts over those of soil science, anthropology, and civil engineering”; and that I agree that there should be an increased focus on experimentation and testing within landscape architecture (

I’ve been arguing that for years).

I hope this discussion continues.

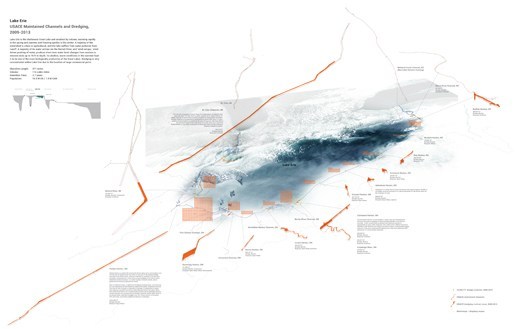

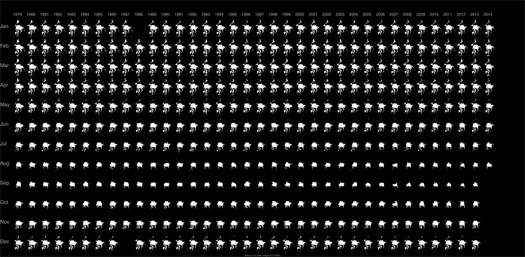

The Dredge Research Collaborative is inviting participants to

The Dredge Research Collaborative is inviting participants to

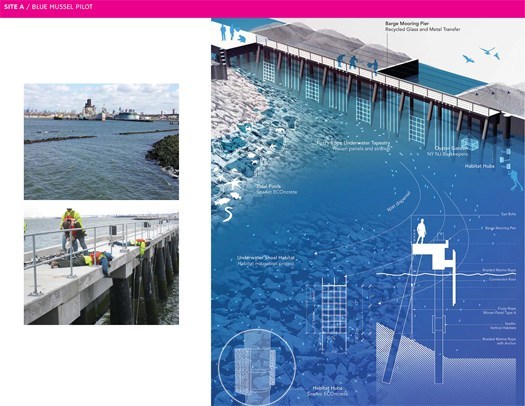

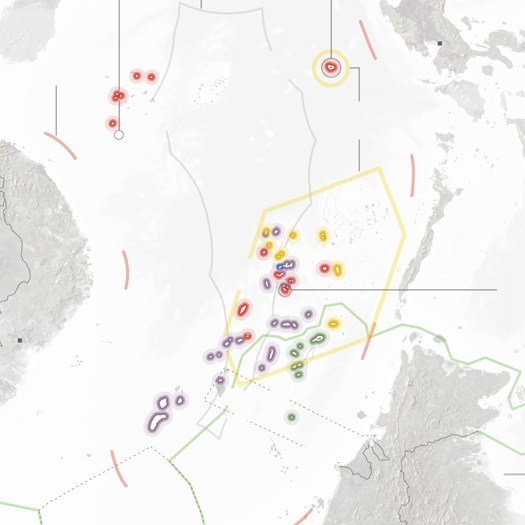

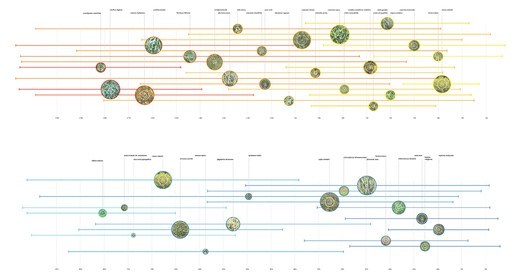

[Two images from artist

[Two images from artist

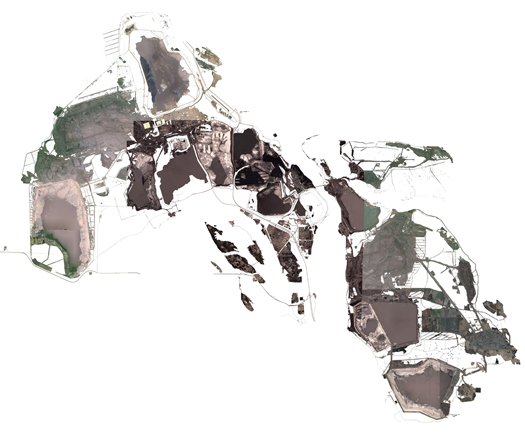

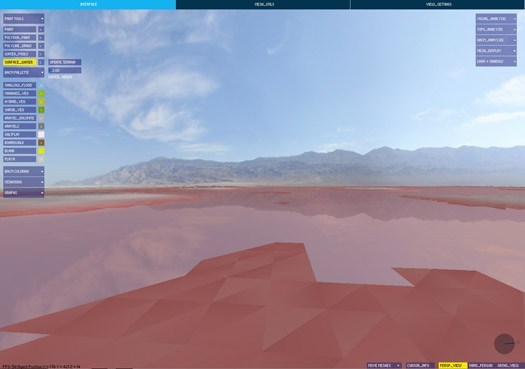

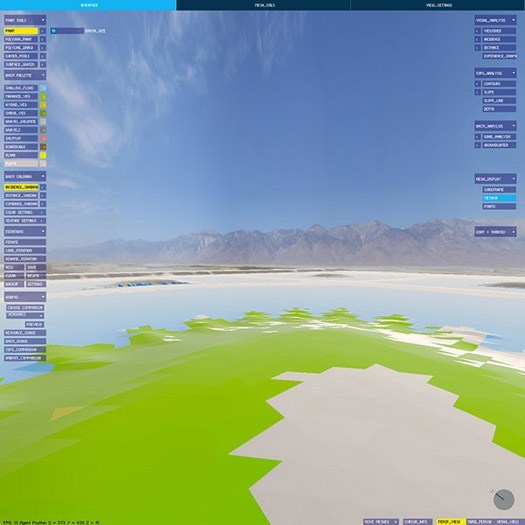

[As a Friday return to blogging for mammoth, photographs of

[As a Friday return to blogging for mammoth, photographs of