<figure>

© Mikaela Burstow

© Mikaela Burstow

- Architects: AAU ANASTAS

- Location: Jericho, Palestine

- Research Lab: SCALES, GSA Lab ENSA Paris-Malaquais

- Area: 62.0 m2

- Project Year: 2017

- Photographs: Mikaela Burstow

© Mikaela Burstow

© Mikaela Burstow

From the architect. Palestine suffers of a misuse of stone as a structural material: while it was an abundant material used for structural purposes in the past, it is now used as a cladding material only and the know-how of stone building is disappearing. The research aims at including stone stereotomy – the processes of cutting stones – construction processes in contemporary architecture. It relies on novel computational simulation and fabrication techniques in order to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language.

© Mikaela Burstow

© Mikaela Burstow

Our research department – SCALES – and GSA (Geometrie Structure Architecture) lab are leading this research on stone construction techniques. The results of the research will

© Mikaela Burstow

© Mikaela Burstow

Beyond the scientific and technical issues that make Stonematters a unique object, the project represents as well a cultural challenge: it has been entirely built with available know-hows in a peripheral zone of the culturally marginal city of Jericho. Processes of several factories have been combined in order to use existing known techniques for new uses. The polystyrene blocks, for example, have been roughly cut in a factory and transported to another for a robotic carving process. Right after its completion Stonematters attracted curious inhabitants of Jericho and elsewhere in Palestine, putting together the seeds of the future el-atlal artists’ and writers’ residency. Through the understanding of our historical cities the research tries to link techniques of constructions to urban morphologies. It puts a non-hierarchical hypothetical link between the scale of stereotomy and the scale of urban fabric. In that context, the idea is to suggest new urban morphologies linked to the scientific use of a largely available material in Palestine.

© Mikaela Burstow

© Mikaela Burstow

Stone in Palestine In Palestine, the most common construction material is stone. Stone is abundant, widely available and – foremost – an urban law imposed by the Ottomans requires stone construction in order to unify the built landscapes. This law underlines the shift from a self- managed urbanism to an authority urbanism.

© Mikaela Burstow

© Mikaela Burstow

Not only is the stone a marker of the transition in the urban and social structures, but it shows the evolution of the Palestinian city’s morphology. The construction techniques’ evolution, from fabrication to implementation, has an effect on the entirety of the Palestinian city. The church of Sainte Anne is one of Jerusalem old city’s most valuable witness of crusaders’ architecture. The church has been built in the 12th century by the Crusaders. The church of Saint Anne offers a complete example of what was the architecture of the Crusaders in Palestine; a combination of different architectural elements that they brought from abroad and indigenous elements that they found in situ.

© Mikaela Burstow

© Mikaela Burstow

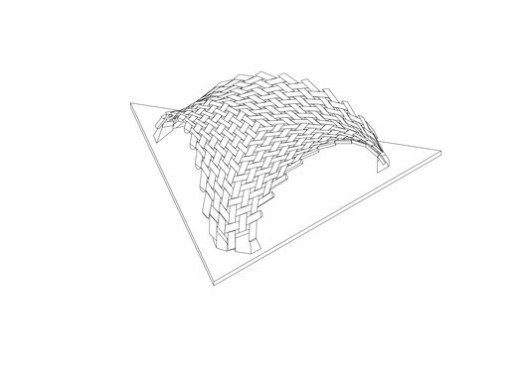

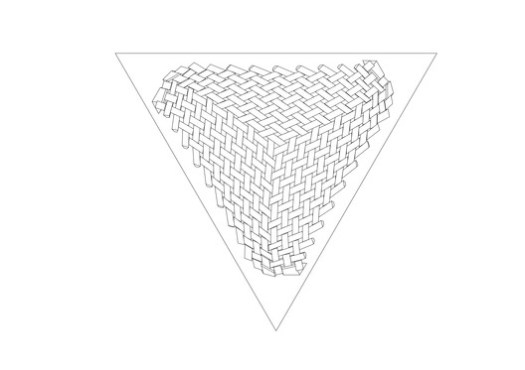

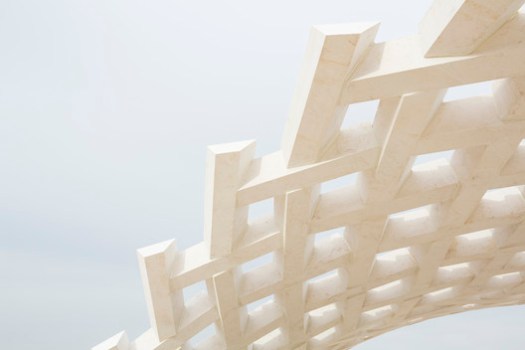

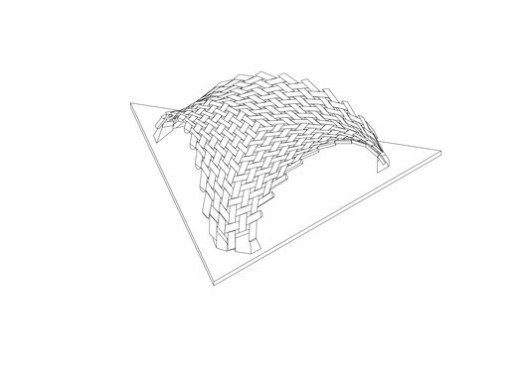

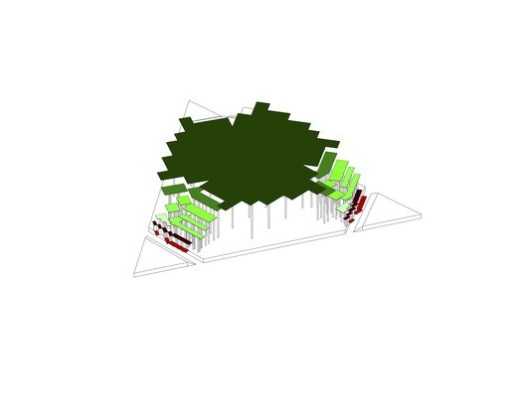

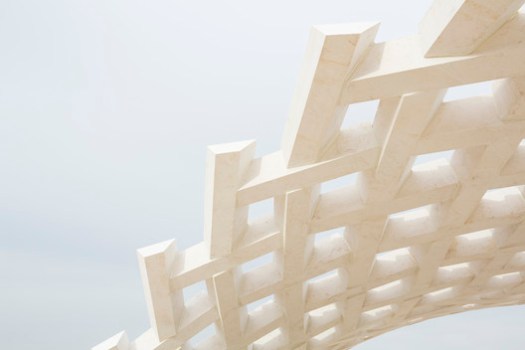

Stone Matters The vault covers a surface of 60 m2 and spans 7 meters with a constant depth of 12 cm. The geometry follows the shape of a minimal surface on which geodesic lines are drawn and set the pattern of the interlocking stones. The whole structure is made of 300 mutually supported unique stone pieces.

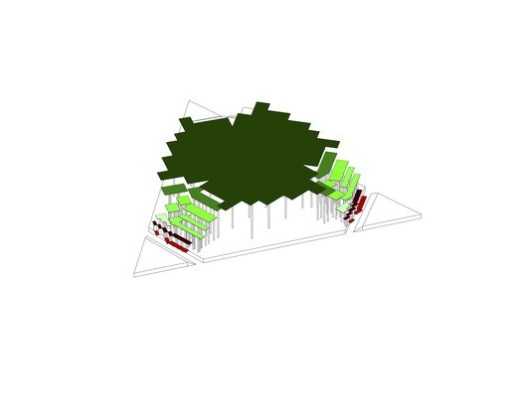

Axonometric

Axonometric

© Mikaela Burstow

© Mikaela Burstow

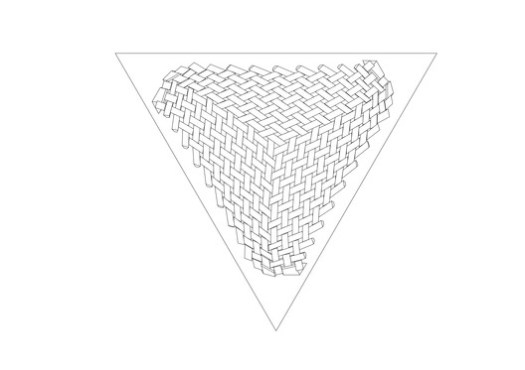

Plan

Plan

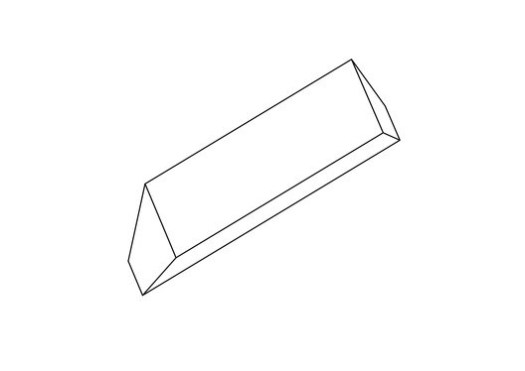

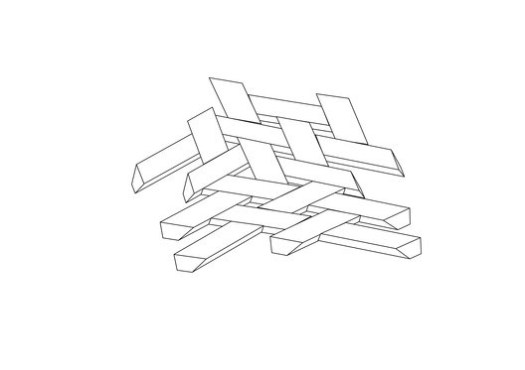

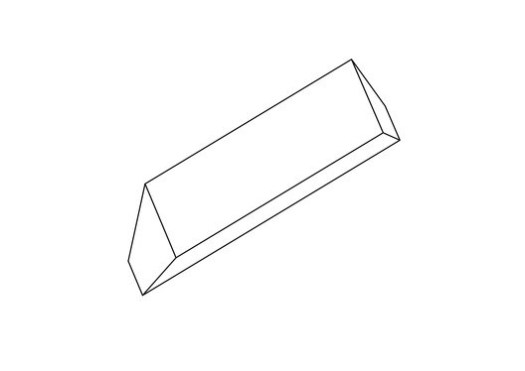

Stone Cutting The geometry of the vault follows the shape of a minimal surface on which geodesic lines are drawn and set the pattern of the interlocking stones. The whole structure is made of 300 mutually supported unique stone pieces. Each stone has 4 incliced interfaces, that allow the assembly of the different stone voussoirs.

© Mikaela Burstow

© Mikaela Burstow

Based on geometrical parameters as the overall shape, the density of the paving, the inclination of contact surfaces, the size of the voussoirs, and number of voussoirs types, a specific structural criteria can be improved.

Stone Geometry

Stone Geometry

© Mikaela Burstow

© Mikaela Burstow

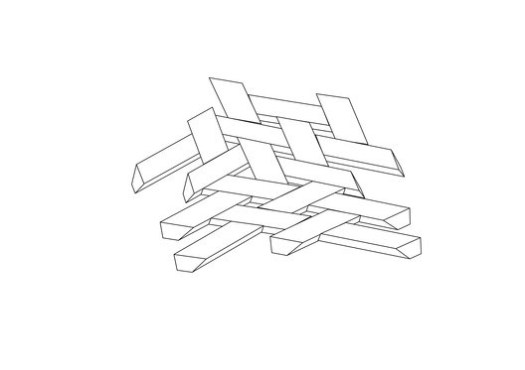

Stone Assembly

Stone Assembly

Formwork Carving The formwork of the vault is made out of blocks of polystyrene of variable heights, carved with the shape of each stone. When arranged together they form a continuous counter-form of the entire structure. On each block, stones are referenced and placed at their exact position.

© Mikaela Burstow

© Mikaela Burstow

Formwork Diagram

Formwork Diagram

© Mikaela Burstow

© Mikaela Burstow

Formwork While the polystyrene blocks were digitally cut using robots, the main formwork was created by the local artisans using usual wooden formworks. Different altimetries were defined, generating a stepped formwork that receives the carved polystyrene blocks.

© Mikaela Burstow

© Mikaela Burstow

Stone Mounting Stone voussoirs are assembled on the mounted polystyrene blocks. Each stone’s location is defined on the formwork. The mounting started from the upper center of the vault progressively advanced towards the edges in a concentric process. The inclined interfaces between the stone voussoirs generate the interlocking system of the structure.

© Mikaela Burstow

© Mikaela Burstow

© Mikaela Burstow

© Mikaela Burstow

© Mikaela Burstow

© Mikaela Burstow

Displacement Spanning 7m, the vertical displacement of the vault has been delicately controlled. The initial shape has been adjusted several times, adding a counter jib in the center of the gyroid form, increasing the curvature thus reducing the displacement.

Dismantling of the Scaffolding The dismantling of the scaffolding was sequenced by different steps. Laboratory glass plates were first installed at few locations of the structure, allowing the measuring of the movements of the structure during the un-mounting of scaffolding. The formwork jacks were then taken down of a few centimeters, letting the whole structure hold by itself. After a few hours, the glass plates were inspected, and no brakes were visible. The scaffolding was gradually taken off.

© Mikaela Burstow

© Mikaela Burstow

© Mikaela Burstow

© Mikaela Burstow

Opening The el-Atlal project is meant to be a model of construction techniques. It allows to envision new possible cities’ morphologies, new construction techniques and a sophisticated use of stone. The project has the ambition of creating a mode of urbanism, and as the harat succeeded in building a city that fits their needs through stone construction techniques, el-Atlal expects to be a breeding ground of inclusive approaches to Palestinian urbanism. An urbanism whose scales are profoundly associated. A technical and durable urbanism leaving a trace on the city’s evolution and on the Palestinian landscape.

© Mikaela Burstow

© Mikaela Burstow

Until the beginning of the previous century stereotomy, or the art of cutting and assembling stones, played an important role in the esthetics as well as in the structural construction principles. Today’s stone factories only produce standardized blocks of few cm, used as cladding of a reinforced concrete structure. The techniques used for building with stone have an effect on the speed of construction, the urban spread of territorial boundaries, and the morphology of all buildings. In other words, stereotomy and the construction methods leave a trace on the palestinian landscape.

© Mikaela Burstow

© Mikaela Burstow

© Mikaela Burstow

© Mikaela Burstow

Reinvigorating stereotomy as a way of optimizing structural performance using advanced design simulations is the founding principle of stone matters. Based on geometrical parameters as the overall shape, the density of the paving, the inclination of contact surfaces, the size of the voussoirs, and number of voussoirs types, a specific structural criteria can be improved. The whole process is an in-progress workflow which will aim at using computational design and advanced fabrication techniques in order to present a modern stone construction technique as part of a local and global architectural language.

© Mikaela Burstow

© Mikaela Burstow

<img src="http://feeds.feedburner.com/~r/ArchDaily/~4/GDSLVgeDbnY" height="1" width="1" alt=""/>